Many moons ago when I was an awkward little scrap of a girl, I was hustled along on my first school trip to a gallery. Entirely uninterested in whatever it was we were destined to see, I managed to creep away from the group. Drawn to the colourful, crowded gift shop, I found my first true inspiration. Rows of gorgeous serene postcards and prints of Georgia O’Keeffe’s flowers and landscapes. I can barely describe the feeling, it was like discovering treasure! I could not fathom why they were all looking at that dusty old stuff when magic existed here in abundance! Drawn in particular to the flowers, and unable to leave without, or choose between them, I spent all my lunch money 6 Postcards. Oh! To be able to create something that beautiful! And so, I became inspired to pursue art.

Georgia was born in Wisconsin in 1887,almost 100 years before I’d find her prints on my school trip. And now that I know more about her, I appreciate her work all the more. She was so fierce and unwavering in her style. She didn’t bend to the fashions of the time, but stayed true to her methods and pursuits. And despite being unwell for lengthy periods, she still managed to produce over 2000 paintings in her lifetime.

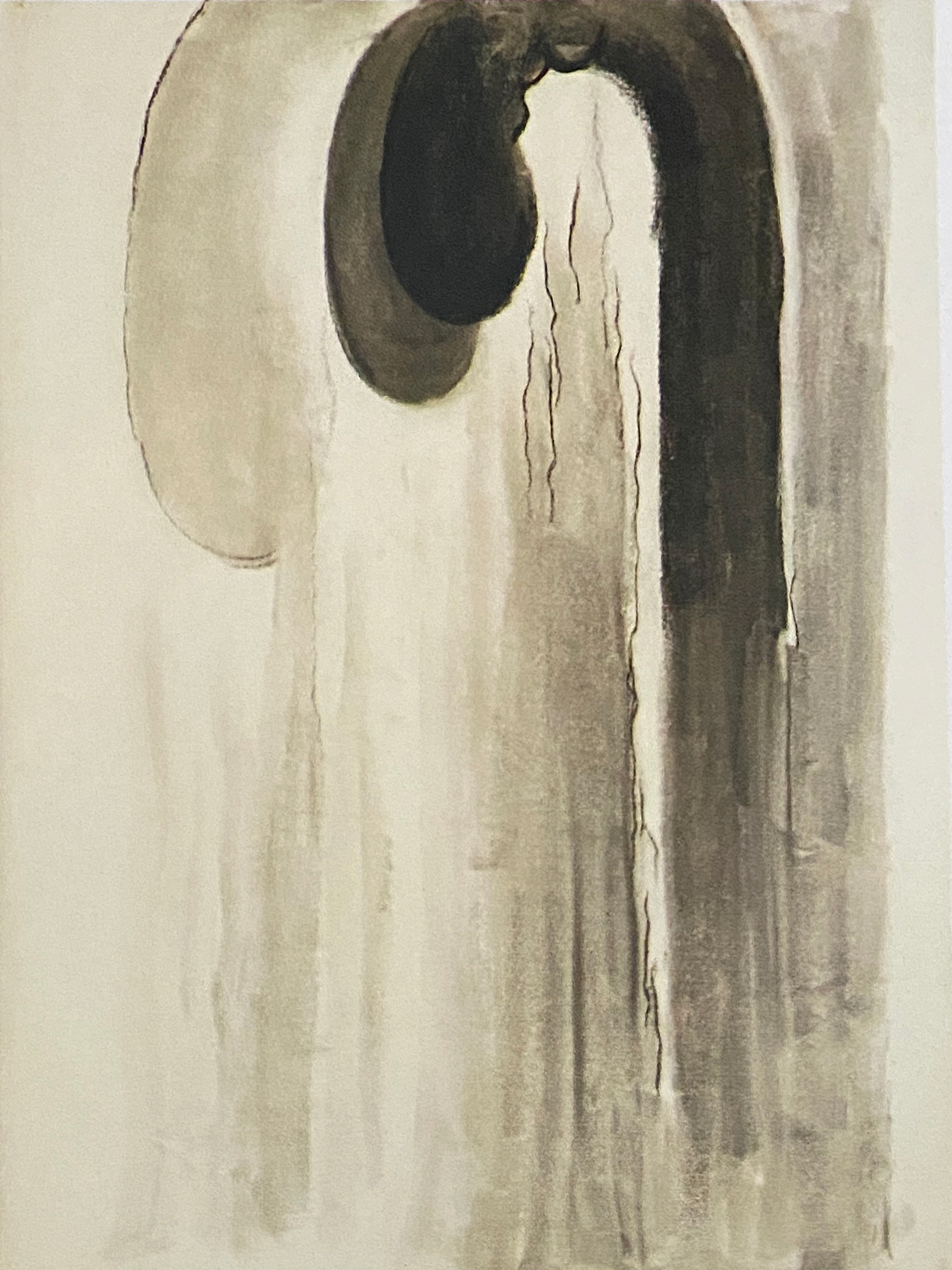

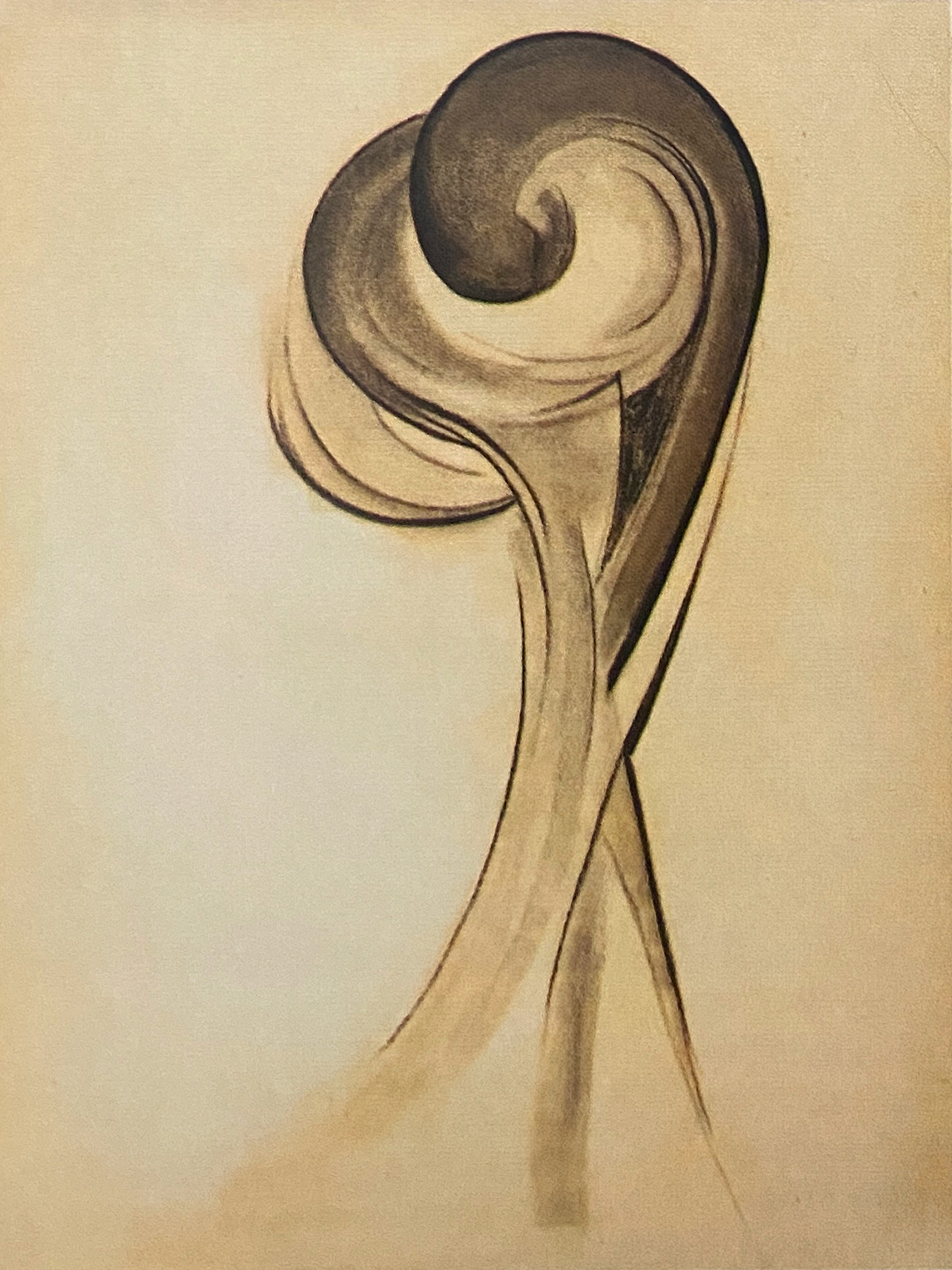

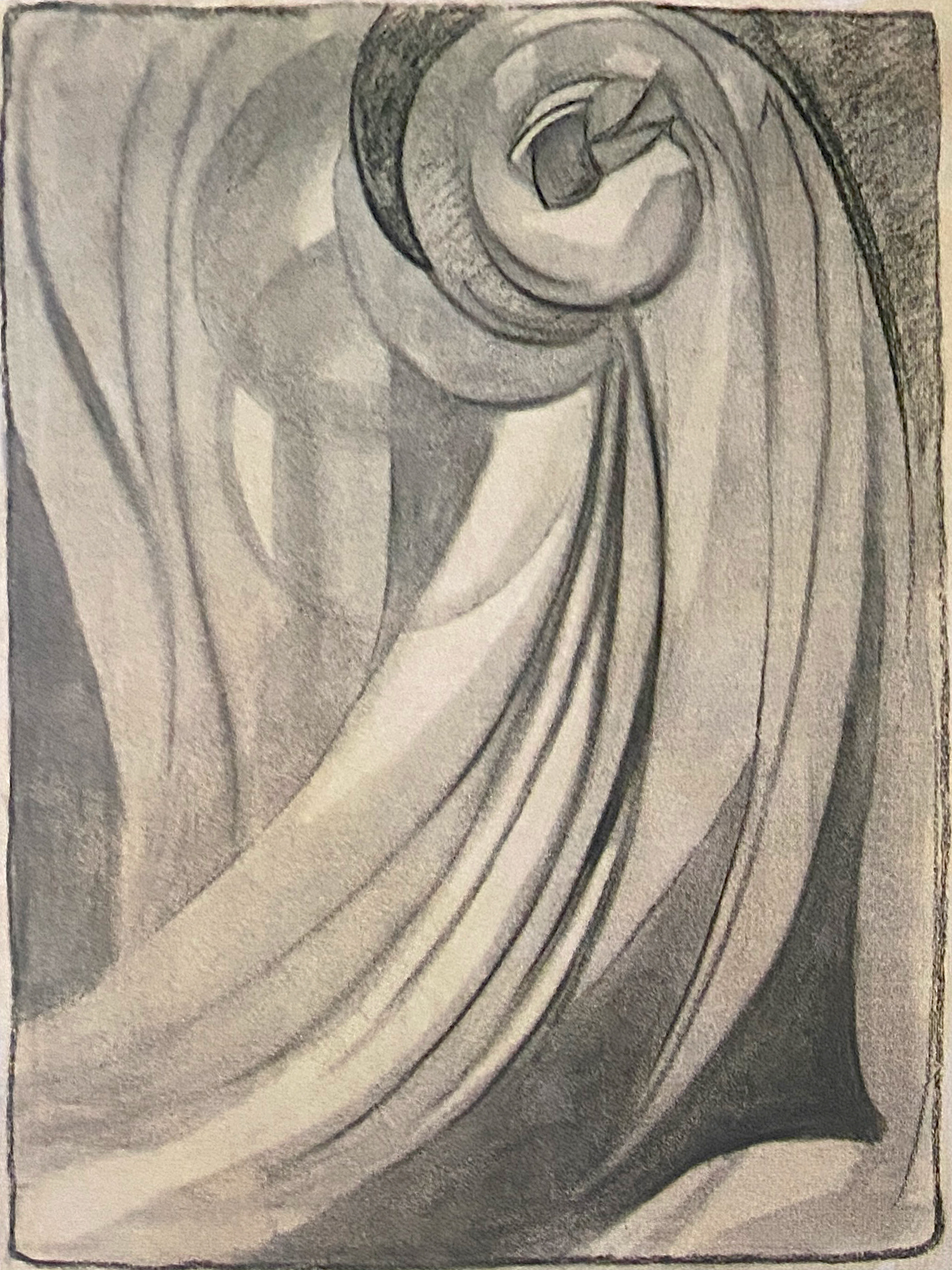

From 1905 until about 1920, she studied art or earned money as a commercial illustrator or a teacher to pay for further education. Georgia began to develop her unique style with abstract watercolours and charcoal drawings. She was deeply influenced by Modernist artist and teacher, Arthur Dow, who taught her to interpret her subject matter rather than trying to represent it accurately. Although a brilliant Realist painter, Georgia boldly embraced this radical style of Modernism. This was a movement that believed art should be an intellectual and imaginative process, where art is a personal expression. She experimented with abstraction for two years while she taught art in West Texas.

"I had to create an equivalent for what I felt about what I was looking at – not copy it." - Georgia O'Keeffe

Through a series of abstract charcoal drawings, she developed a personal language to better express her feelings and ideas. O’Keeffe mailed some of these highly abstract drawings to a friend, suffragist Anita Pollitzer, in New York City. Anita showed them to Alfred Stieglitz, who was so taken by them that without meeting Georgia, or even getting her permission, he made plans to exhibit her work. The first that the artist heard about any of this was from another friend who saw her drawings in the gallery in late May of that year.

She finally met Stieglitz after going to his gallery and chastising him for showing her work without her permission. He was a wealthy and influential art dealer and photographer, who pursued younger women. At the time he was married to Emmy Obermayer, nine years his junior, who was also wealthy and financially supporting both the family and his business, despite his open resentment toward his wife. He’d been photographing his daughter Kitty with increasing intensity for many years. He made it his goal to document her entire life in photos. Emmy tried very hard to put an end to it. She felt he was ruining their daughter’s life by following her around with a camera.

Georgia was at the time exchanging romantic letters with Paul Strand. When Strand told Alfred about his interest, Stieglitz responded by confessing his own infatuation with her. Gradually Paul's interest waned, and Alfred's escalated. By the summer of 1917, despite the 23 year age gap, Alfred and Georgia were exchanging "their most private and complicated thoughts" by letter.

In 1918, Georgia relocated to New York after Alfred promised he would provide her with a quiet studio where she could paint. Within a month he took the first of many nude photographs of her at his family's apartment while Emmy was away, but she returned while their session was still in progress. Emmy already suspected something was going on between the two, and demanded he stop seeing Georgia, or get out. Alfred left immediately and found a place in the city where he and Georgia could live together. Ultimately Georgia was not only Alfred’s new romantic partner, she was also to replace Kitty as his muse for this lifelong documentary project.

Alfred photographed Georgia obsessively, capturing every part of her changing body over the course of about two decades, beginning when she was 30 and he was 53. In this highly prolific period, he produced more than 350 mounted prints of Georgia that portrayed a wide range of her character, moods and beauty. He shot many close-up studies, especially her hands either isolated by themselves or near her face or hair. In her words “He photographed me until I was crazy.” This is why I don't want to use his photos here. There's an element on non-consent that makes me personally uncomfortable, even though there are many in the public domain.

Georgia is best known for creating her stunning large-scale paintings of natural forms and flowers at close range. Over the years, her subjects included New York skyscrapers, flowers, New Mexico landscapes, and bones and skulls. It amazes me that she was able to create so passionately despite the stresses she was under. Perhaps her art was her refuge.

Georgia wanted a child, but Alfred, nearing 60, had no interest. This was complicated by the fact that in 1923, Kitty had a child, after which she experienced severe postpartum depression. The family blamed Alfred’s affair and the messy divorce for Kitty’s breakdown. He married Georgia within 4 months of the divorce. Kitty was institutionalised for 48 years, until she died in 1971.

In the summer of 1929, O’Keeffe made the first of many trips to northern New Mexico. The stark landscape and Native American and Hispanic cultures of the region inspired a new direction in O’Keeffe’s art. For the next two decades she spent most summers living and working in New Mexico. She made the state her permanent home in 1949, three years after Stieglitz’s death.

O’Keeffe’s New Mexico paintings coincided with a growing interest in regional scenes by American Modernists seeking a distinctive view of the nation. In the 1950s, O’Keeffe began to travel internationally. She painted and sketched works that evoke the spectacular places she visited, including the mountain peaks of Peru and Japan’s Mount Fuji. At the age of seventy-three, she took on a new subject: aerial views of clouds and sky.

She would work with her subject matter over and over, often for decades, until many became abstracted. One subject she kept returning to was the mountain outside her home, which she adored. Georgia died in Santa Fe on March 6, 1986, at the age of 98. Her ashes scattered in the beautiful landscape she called home.

Cerro Padernal, viewed from Ghost Ranch "It's my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it"